As an Accessibility Community Consultant with Siteimprove, and as a totally blind screen reader user, I am often asked what I think about accessibility overlays. As someone who has been using a screen reader for 35 years, I can tell you that accessibility overlays are not the accessibility solution they claim to be.

What are accessibility overlays?Accessibility overlays are automated add-on solutions that inject accessibility fixes using JavaScript snippets directly into your website instead of updating the source code. Usually, overlays come in the form of a toolbar, plugin, app, or widget. There are also custom overlay solutions, which are tailor-made overlays that promise to address the shortcomings of your publishing system better than generic overlay tools. While these custom solutions are specific to your site’s code, they still do not change the existing code.

Overlays are not the miracle solution to accessibility

I have encountered overlays on several websites. Most of them claim to be a “magic bullet” for accessibility. They state that if you apply a simple JavaScript to your website, all accessibility issues will be resolved, and you will be compliant with WCAG 2.1 guidelines. Most of them are fairly cheap to implement, so some companies are tempted to use overlays as their accessibility solution of choice rather than spend the time and resources necessary to make true accessibility fixes.

Overlays lull stakeholders into thinking they don’t have to care about accessibility.

Overlay tools seem to become increasingly popular as businesses realize they need to have an accessible website – whether for legal or ethical reasons – but lack the resources or knowledge to properly address accessibility issues. To avoid getting sued under the ADA, they turn to overlay tools as an out-of-the-box fix, which is no surprise as it sounds appealingly simple. Accessibility overlay vendors will make countless false promises guaranteeing that your website will be 100% accessible, and let you walk away thinking you’ve done your due diligence. In reality, however, these tools are limited in scope and fail to offer a full compliance solution (there’s an increasing number of lawsuits against companies using overlay plugins).

Using these overlays is like putting a band-aid on accessibility problems. They offer no true solution for the accessibility issues they claim to fix. If the company decides not to work with the overlay provider, the JavaScript disappears and thus the “fixes” go with it. In addition, by not fixing the problem in the code, the organization does not learn what causes accessibility problems and will find it difficult to avoid the occurrence of the same issues over and over again. That’s why inclusive design from the ground up offers a tremendous benefit: You learn to identify accessibility barriers and how to remove them, and you can then share your knowledge across your teams. It’s a learning opportunity for the entire organization.

How can you fix what you can’t detect?

As a screen reader user, I find that these accessibility overlays often fail to do what they claim to do. For example, I often detect unlabeled graphics and buttons on sites that have overlays and are supposed to be 100% compliant with WCAG 2.,1. This is not surprising, as overlays, being automated tools, can only detect around 30% of the errors on a site.

Overlays are a superficial solution that fails to make any meaningful accessibility improvements.

The shortcomings of accessibility overlays are well known in the accessibility industry – they can detect and automatically fix only 30% of accessibility barriers occurring on your website. This means that 70% of WCAG issues will go unnoticed and require manual testing to be remediated (some vendors claim to afford manual testing and remediation, however the remediation is only applied to the overlay layer, not the underlying source code):

- Unlabeled and mislabeled form fields

- Disabled zoom

- Minimum width

- Use of layout tables

- Ambiguous anchor text links

- Images of text

- Focus order

- Alt text

- Missing links

- Misidentified language

- Closed captions

- Locked display orientation

- Consistent identification

- Keyboard only usage

- Keyboard traps

- Error prevention

- Error suggestions

- Incorrect heading structure

Overlays fail to create a truly equal browsing experience

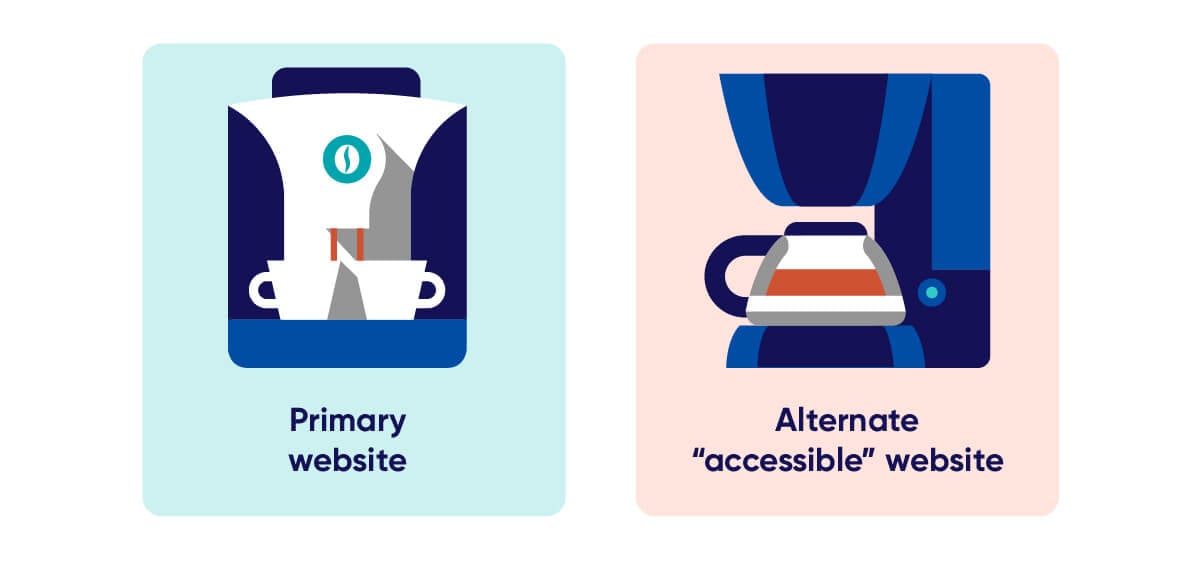

Another issue I have with overlays is that they offer a “separate but equal” experience to users with disabilities. Their JavaScript alters the website for users with disabilities in ways that create a separate user experience. As a totally blind screen reader user, I can tell you that I do not want a “separate but equal” experience. Instead, I want to be able to browse the website without alterations being made to it, just like my non-disabled peers.

Alternate “accessible” websites

Overlay solutions typically provide a button that links to a separate website claiming to offer an equal, accessible experience. In practice, these accessible websites provide a reduced navigation, features, and content, thereby creating a truly separate, different experience for users with disabilities. This opposes ADA’s core intent to create full, equal enjoyment (source: Accessibility.Works).

Overlays and data privacy

Another concern I have is privacy. Somehow, these overlays seem to know that I am a screen reader user. Most of them come up with the keyboard shortcut for accessing the special accessibility menus, and this is a problem for me. If these overlays can tell that I am using assistive technology, are they giving information to the business that I am a user with a disability? While I don’t believe this to be the case, I am uncertain, and so this is yet another reason I do not use these accessibility products.

Overlays don’t protect you from lawsuits

Also, overlays do not offer immunity from legal action, though they claim to offer 100% compliance with WCAG 2.1. Several companies which use these overlays have found themselves involved in an accessibility complaint or lawsuit. In addition, companies that have been sued have found that the company producing the overlay does not cover costs incurred from the legal action.

Is there ever a place for accessibility overlays?

Perhaps. Overlays could be useful if they were implemented as a short-term fix with the full intention of fixing the problems in the code of the website as soon as possible. But, while this might be acceptable, I know that – unless I absolutely have to use the site in question – I will exit any site with an accessibility menu and go to a competitor’s site. This could affect businesses or financial institutions negatively if other customers with disabilities feel the same way.

In summary, the old adage rings true again. “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.” In my opinion, the use of accessibility overlays should be avoided at all costs.

Don’t know where to start with accessibility?

If digital accessibility sounds overwhelming to you, then a good place to start is by getting an overview of where your site stands. Use our free website accessibility checker to see where you’re doing well and where there’s room for improvement.